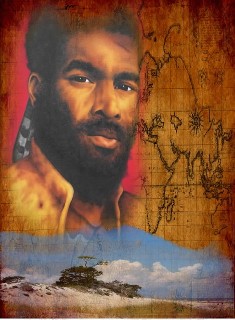

Estevanico - 'The Moor'

The Americas' Greatest African Explorer

Estevanico: Sold, to replace the Fish!

The first historically significant slave in what would become the United States was Estevanico, a Moroccan slave and member of the Narvaez Expedition in 1528 and acted as a guide on Fray Marcos de Niza’s expedition to find the Seven Cities of Gold in 1539. Estevanico became the first person from Africa known to have set foot in the present continental United States.

Estevanico; also known as Estevan, Esteban, Estebanico, Black Stephen, and Stephen the Moor, was born in Azamor, Morocco around the year 1500. In 1513, the Portuguese took control of this area. When they fell on hard times during a drought in the early 1520s, the Portuguese started selling Moroccans as slaves to European customers. Estevanico was sold to Andres de Dorantes. Estévanico was fluent in many languages spoken in Spain, including Arabic, Spainish, Berber, and Portuguese. This ability allowed Estevanico and Andres de Dorantes to develop a very positive relationship, and the two were said to be friends.

Dorantes dreamed of sailing to the New World and he sought to take Estevanico with him. Estevanico was raised as a Muslim, but because Spain did not allow non-Catholics to travel to the new world, Estevanico was converted to Roman Catholicism. In 1527, Dorantes signed them up to join an expedition organized by Pánfilo de Narváez to conquer the unexplored territory between Florida and Mexico, along the Gulf of Mexico. Narváez had twenty years of experience in conquering Mexico, and Spain had just appointed him Governor of the unconquered Florida. Hurricanes caused the crew to spend the winter in Cuba until they recouped and could travel safely. After more severe weather, on April 12, 1528, Dorante and Estévanico landed on the shores on Florida with more than three hundred other men, including Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca and Alonso del Castillo Maldondo. They landed just north of Tampa Bay.

Narváez and his crew were given many gifts and food by the first natives they met. Feeling confident, he set out to claim the land with a compliment of three hundred men and 40 horses. After three months of traveling in hostile land and encountering hostile natives, they arrived in Aute, with no sign of their ships. With disease and desperation running high, the leaders became determined to see civilization again and set out to build five watercrafts. After six weeks, they had eaten all of their horses and on September 22, 1528 loaded fifty men on each barge and set sail, near what is now Apalachiiocola. Two days later, Estévanico's company was left with nothing but maize and water held in bags made of rotting horse skins. Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca wrote of this journey, "So great is the power of need that it brought us to venture out into such a troublesome sea in this manner, and without any among us having the least knowledge of the art of navigation." The men all tried to keep their boats within sight of land. On October 27, 1528, the explorers landed in what would become American First Settlement; Pensacola, Florida. They were greeted by friendly natives and traded all their corn for fresh water and seafood. They were allowed to stay the night and invited them to sleep in a lodge house of 300 men. After an altercation the Spanish explorers were forced to leave Pensacola the following morning, October 28,1528. The men drifted for several days and eventually were caught off-guard by the strong currents at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Slowly, the boats separated and disappeared from the sight of each other. Governor Narváez’s boat drifted out into the Gulf of Mexico and become lost.

Dorantes' boat eventually capsized near what is now Galveston, Texas; where they joined the group led by Cabeza de Vaca . The combined group numbered 80 . In de Vaca ‘s journal , he recorded that the Native Indians felt so sorry for the miserable crew that they wept. In a relationship balancing between pity and fear, the men spent the winter on the island they named Malhado (Misfortune). After the winter ended, only 15 men were left. It was reported that a group of Spaniards committed the horror of cannibalism in the presence of the natives.

In April 1529, Estévanico, Dorante and Castillo gathered the survivors from their original group and left Cabeza de Vaca's company behind. The Natives in the area accepted the men, but eventually enslaved them for more than five years. During this time, five men died from trying to escape, while more died from disease and hunger.

By 1534, only four were alive: Estevanico, Dorantes, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and Alonso del Castillo Maldonado. (The most famous of those is Cabeza de Vaca, whose writings are an important source of information on the Americans of the 16th century.) In 1535, they finally escaped and interacted with other natives to survive. They used their healing skills to befriend them. This was not a skill of science, but herbal medicine and prayer. Estevanico soon gained the reputation as a healer and was called upon to heal everything from headaches to people near death. Not only did this make them friends with the locals, but also, it ensured their survival and created a reputation that opened up the opportunity for travel again. Estévanico also helped the group with his ability to learn more than six Indian languages. The Spaniards wanted to maintain their mystique and authority, so Estévanico was constantly among the Indians acting as ambassador for the group.

With the aide of thousands of Indians, they made their way west by way of the Rio Grande, Presidio, and crossing into Mexico at what is now El Paso. They were nicknamed ""children of the sun" by the Indians, because the men traveled from east to west. Because their reputation was so great, when a patient died, the people assumed the fault was with the patient. In May of 1536, they arrived at San Miguel de Culiacan (Sinaloa, Mexico). In July, they arrived in Mexico City, the four survivors told stories of wealthy indigenous tribes to the North and this created great interest in the city.

While the other three men all returned to Spain, Estevanico was sold to Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain, who used Estevanico as a guide in expeditions to the North. In 1539, Estevanico was one of four men who accompanied Marcos de Niza as a guide in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, preceding Coronado. Estevanico traveled ahead of the main party with a group of indigenous servants instructed to send back crosses to the main party, with the size of the cross equal to the wealth discovered.

One day, a cross arrived that was as tall as a person causing de Niza to quickly progress forward. Estevanico had entered the Zuni village of Hawikuh (in present-day New Mexico) and for some reason offended the inhabitants so they killed Estevanico and his indigenous servants were sent from the village. De Niza reportedly witnessed the results and quickly returned to New Spain. The exact reason Estevanico was killed is not precisely clear, but accounts suggest the Zuni did not believe his account of representing a party of whites, and further that he was killed because Estevanico was black and wore feathers and rattles, and may have looked like a wizard to the Zuni. Another theory, published in 2002, claims that Estevanico was not killed by the Zuni, and that he and friends among the Indians faked his death to achieve his freedom.